I was lucky enough to attend Dr. John Borgonovo's talk on Cork Labour and the Irish Revolution, held in Solidarity Books on the 17th of May. John is the author of

Spies, Informers and the 'Anti-Sinn Fein Society': The Intelligence War in Cork City, 1919-1921, the forthcoming

The Battle for Cork: July - August 1922 and is a respected authority on revolutionary Cork. The talk attracted 20-30 people and was very informative. John talked solidly for an hour before there was a lively question and answer session. This report is based on my own hastily scribbled notes but I have tried to be as accurate as possible. Any comments of my own are in italics.

The Irish Revolution

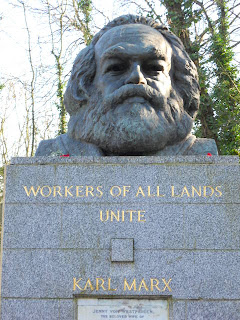

The effects of the first world war can be compared to both the fall of the Berlin wall and the contemporary 'Arab Spring.' There is a similar dynamic at work in all three. The impact of WW1 on Ireland was similar to the impact it had on the rest of the continent. The Irish revolution has rarely been examined within this european context but rather as an insular phenomenon. Similarly, the Labour radicalism that coincided with the revolution has not been included in the dominant narrative.

Cork Before the War

The organised Labour movement in Cork at the start of the twentieth century

was dominated by craft and artisan unions. Very few unskilled workers were organised and the limited franchise meant that there was, as of yet, little in terms of an electoral working-class. Nationalist politics were also divisive and contributed to maintaining a diffuse labour movement. Half of the city lived in extreme poverty, living in tenements and barely staying above starvation levels. 25% of the population were unskilled labourers with no job security. These conditions created a culture of fear, shame and poverty which was difficult for unions to organise in. In addition, the existing craft unions were highly insular and unsympathetic towards unskilled workers. The Cork trades council had been founded in 1890 but was weak. Cork politics, industry and civil society were dominated by unionists.

The two main political forces in the city were the All for Ireland League (linked with the land and labour association) and the Irish Party or Redmondites. The rivalry between the two groups was bitter but by 1914 the Irish Party had emerged as the dominant force in the city. The Redmondites had close links with the clergy, the mercantile Catholic middle-class and were characterised by corruption and intricate patronage networks. IPP hegemony in Cork was almost comparable to a one-party state. They controlled both papers in the city, while the paramilitary Irish volunteers and semi-military Ancient Order of Hibernians were almost wings of the Redmondite party. Redmond is traditionally regarded as a peaceful moderate statesman. I'm dubious however. The Redmondites did not tolerate dissent and there was often widespread electoral violence in Cork.

Republicanism was a marginal force. However, there was a strong republican tradition in the city. Cork had been a Fenian stronghold and there was, at one point, 4,000 fenians in the city, most of them working-class. Republicanism was weakened after the turn of the century but was still capable of mobilisation, organising demonstrations against the Boer war, the royal visit and well attended Manchester martyr commemorations. The Labour Party didn't exist at this point as a political party, It was more of a loose interest group that also ran candidates. In the 1908 local elections the Labour Party only won 6 of 50 seats on the corporation. The 1908 dock strike was a critical event for Cork labour, albeit one that has been overlooked in Irish labour historiography. The strike was very divisive and there were violent scuffles between strikers and scabs. Apparently, Connolly was influenced in his formation of the Irish Citizen Army by the anti-scab tactics of the Cork dockers. After the strike, the ITGWU was temporarily crushed in Cork. The dock strike split the trade union movement in the city and two new trades councils were formed. The Cork district trade council was composed of the old craft unions, was conservative and supported the IPP. The United Labour council was more progressive and supported the All for Ireland League. The Land and Labour association also experienced a split. The trades council wasn't reunited until 1916. There was no unified idea of Labour in Cork and no political vision until Larkin in 1913 / 1914.

There was a cadre of radicals in existence in the city consisting of labour radicals, suffragettes and republicans, who all formed part of a radical mileu. There was a lot of cross-polination of ideas and cadres were developed, despite a lack of widespread support. As such, by the outbreak of WW1, republicans were well placed to take advantage of the situation.

World War One

When war broke out the city was largely pro-war. 7,000 enlisted in the army, the vast majority of them working-class. Working-class areas were strongly pro-war and the wives of soldiers, known as seperation women, were vocal in their support of the war effort and were active politically. While the majority were pro-war, Labour radicals and republicans opposed it. Trade union leaders also tended to be pro-war.

WW1 destabilised the country politically and economically. In 1917 revolution broke out in Russia, followed in 1918 by a number of other countries. Cork people looked to these events with interest. Pro-Russian Revolution meetings were held in Cork and republicans, as well as labour radicals, were inspired by these events.

The war led to massive inflation in Ireland. Prices in Cork doubled in 2 years and hit workers and the poor particularly hard. On the other hand, the 7,000 mobilised Corkmen meant that there was less of a labour surplus. Certain industries benefitted and the Cóbh naval base benefitted the city economy. Some things got better and some got worse, but the inflation was hugely destabilising. It wasn't a depression but a climate of economic insecurity combined with the impression that Britain was losing the war. The population began to turn against the war in droves. Republicans had the capacity to take advantage of this thanks to a strong layer of leaders, a simple yet powerful explanation and programme for change as well as mass organisations in the form of the volunteers and cumman na mban.

The trade union movement was also set to benefit from the new situation. Wages couldn't keep up with inflation and the introduction of mandatory arbitration in labour disputes (which generally benefitted the labourers) encouraged the growth of union organisation. Farm workers became organisaed and were often the most radical elements in the labour movement. This took labour beyond the cities and into the countryside. The ITGWU became the vanguard of the labour movement. In 1917 and 1918 strikes became endemic, most of which were ITGWU led. Women workers also became organised. Discontent with the war grew and labour militancy had a spiralling effect with strikes in one industry sparking off strikes in other workplaces. By 1918 strikes in the city had increased by 500%. The Cork working-class were getting organised en masse.

The new political situation saw increased collaboration between the trade unions and republicans. This came to the fore through the people's food committtee. The committee was a response to food and milk shortages and sought to stop or limit food being exported from the city to England. The campaign benefitted from the fact that famine was still in living memory and there was widespread fear that history was about to repeat itself. Pickets were launched, the IRA was involved and for one month there were no live food exports from the city.

At the same time, across the country, rural labourers and republicans were seizing pasture-land to be used for tillage. These were big public events. 100s of people would march behind a band and boisterously seize the land in a carnival atmosphere. This was curtailed when Sinn Féin prohibited its members and IRA volunteers from getting involved. The republican leadership were scared by the militancy of 1918 and the fact that they couldn't control it.

The food scare was brief. Imports resumed as the Allies efforts to curtail U-boat attacks became more successful and there was a good harvest. Prices went down and the panic subsided. Then the city lurched from the food crisis to the conscription crisis. This was more important than the Easter Rising in terms of the revolution. There had been concerns about conscription from the start of the war. Even when pro-war sentiment was high there was still opposition to conscription. In March / April 1918 conscription was introduced and led to mass opposition across all sectors of Cork society. Republicans and the trades council led the opposition. A one day strike was called, the first of 5 such general strikes to occur in the city between 1918 and 1922. There was an anti-conscription rally on Grand Parade which drew 30,000 people. This was probably the biggest demonstration in the history of the city. The Irish Citizen Army was re-organised in the city and 50 - 75 ICA members join the volunteers. The anti-conscription movement threatened to stop food exports, to collapse the banking system by mass withdrawals and that Irish soldiers would refuse to follow orders. Lawyers volunteered to defend the soldiers if their cases went to military tribunals.

There was an explosion in support for the volunteers / IRA. Local leaders of the volunteers had been mainly middle-class (teachers, clerks etc.) before the war, but in 1918 the leadership of the volunteers in Cork became dominated by working-class leaders, many of them trade unionists.

1918 Election

Labour in Cork had by now been integrated into the republican resistance.

In the 1918 election Sinn Féin even offered Labour one of the two seats in Cork, on condition that they would commit to abstentionism. Cathal O'Shannon would have been the candidate had the agreement been made. However, the Labour Party had concerns about the deal. The increased franchise meant the possibility of electoral victory for the Labour Party in Westminster. If the election results meant that a Labour Party victory was contingent upon the support of Irish MPs then the Irish Labour Party leadership was inclined towards ensuring a Labour victory should it occur. However, among the grassroots of Labour there was widespread support for unity of republicans and labour. The Labour leadership's decision not to contest the election was a response to the mood of the rank an file. However, the decision not to run labour candidates as part of a united front for independence was a mistake. Had Labour agreed to this then they could have been more influential later on. From 1919 onwards, Sinn Féin assumed leadership of the movement while Labour lost out. The economic collapse of 1921 and 1922 put Labour on the defensive and the workers movement would never again reach the heights it had achieved in 1918.

Questions and Answers

Q. After Connolly's execution, did the Irish Citizen Army lack a strong left leadership?

A. The ICA still existed during the revolution, mostly among dockers. They were active in gunrunning in particular. The ICA was present in Cork, where it included a women's organisation and boy and girl scouts. The Cork ICA was led by the Wallis', two strongly leftist sisters who ran a shop in Cork.

Q. Were there tensions between SF/IRA and the labour movement in Cork?

A. Local IRA commanders generally saw the revolution in purely military terms and thought little in socio-economic terms. However, the IRA leadership did have a natural antipathy towards the ascendancy. There was also a hostility towards the gombeen men and a loathing of the Redmondites, who were seen as opportunists and whose patronage networks were disliked. The IRA leadership was predominately lower middle-class and many S.F leaders subsequently became virulently anti-communist. Interestingly, some of these figures, like Alfred O'Rahilly and Liam De Róiste, were somewhat left-leaning at the time with progressive attitudes towards the workers movement and even sympathies with the russian revolution. Later on they became extremely reactionary.

For more information see here. Generally, cultural nationalists tended towards conservatism later on in life.

Some IRA leaders thought in left / right terms. Some didn't. Both Labour and the republican movement hated the corruption and patronage networks of the Redmondites though. For example, when MacCurtain became Lord Mayor of Cork he actively reformed the local government system in order to root out the corruption and patronage built up by Irish Party hegemony over the city, lowering the mayor's salary and moving public board meetings to night-time so that labourers could attend.

Q. Why didn't the Union leadership back the strikes occuring in 1922?

There were Harbour and Railroad soviets in Cork in 1922. At the time, there were divisions between 'new' and 'old' labour within Irish trade unionism.

Pun was intentional. In 1920 there was a munitions strike. Docks, railways etc. were closed down to prevent the movement of British war material. This was a wildcat strike, initiated at the grassroots level, that took its inspiration from the 'Hands off Russia' movement in England, where dockers had refused to ship munitions that were to be used against the Bolsheviks. There was a tension between these sort of action and the conservativism of the national executive. The same was true across the pond. For example, at the time of the MacSwiney hunger strike there was a lot of public support in the UK labour movement for taking industrial action in support of MacSwiney. However, his wife Mary, herself a labour activist, was denied permission to speak at the UK LP conference of that year despite (

or because of) the sympathy of the rank and file.

Q. Effect of Civil War.

The civil war broke the labour movement. It occured at a time of high unemployment. In Cork, 20-25% of the city was unemployed at the start of the conflict. This meant there was little appetite for war driven mainly by nationalist ideology. There was even a threat of a general strike against the war. Mass unemployment cut across the development of radical politics and militated against labour militancy.

Q. What was the significance of the Ancient Order of Hibernians and other such societies?

The AOH were a scary organisation. They had 2,000 members in Cork City and 4,000 in the county. They were a very shadowy group with secret committees within secret committees. A significant number of the Irish Party leadership were Hibernians. The AOH was consciously organised as an alternative to the Orange Order. They were dangerous, repellant Catholic supremacists who were more sectarian than any other nationalist grouping. They dissipated outside Ulster after the fall of the Redmondites but many of them later re-emerged into politics after the revolution. I feel that this was part of a counter-revolution and am inclined to agree with that thesis.

Q. What was the role of farm labourers?

Land agitation was almost a continuation of the land war. Many of the most militant strikes in East and North Cork were those of farm labourers, who the ITGWU worked hard to organise. Cork's first May Day celebration saw 20,000 people march behind red flags. Thousands did the same after the election of Robert Day.

Q. Was there a connection between the success of the All for Ireland league in Cork and the turn away from the Redmondites to Sinn Féin?

Many republican leaders came from AFI families. There was a strong antipathy towards Redmond in Cork and huge struggles between the IPP and the AFI were common. Riots occurred at every election; During the 1910 election for example, there were riots for 2-3 weeks. The AFI contributed to Cork's seperatist identity and there was a connection between Anti-Redmondite sentiment in the city and the republican variety of anti-Redmondism that came to the fore in 1918.

Q. Church's attitude towards Labour militancy in 1918/1919?

A. The church turned against the war as it went on and supported the anti-conscription movement. The anti-communism of the Irish Catholic church did not come to the fore until the 1920s. There was clerical involvement in the soviets. Soviet organisers were often very religous and the sight of a rosary being said in a soviet was neither surprising or uncommon.

During this discussion, which was relatively informal, Dr.Donal O'Drisceoil, himself a noted commentator on the war of independence in Cork, occasionally weighed in. As such, some of the notes above may be getting his and John's contributions mixed up. The following I can attribute directly to Donal and it seems a good place to finish the report

D O'D: 1918 represented an important lost opportunity. Republican conservatism has been highly exaggerated. Labour hedged its bets and refused to take a leadership role. It was the fault of the labour leadership, not Sinn Féin and the IRA, that labour had to wait.

End

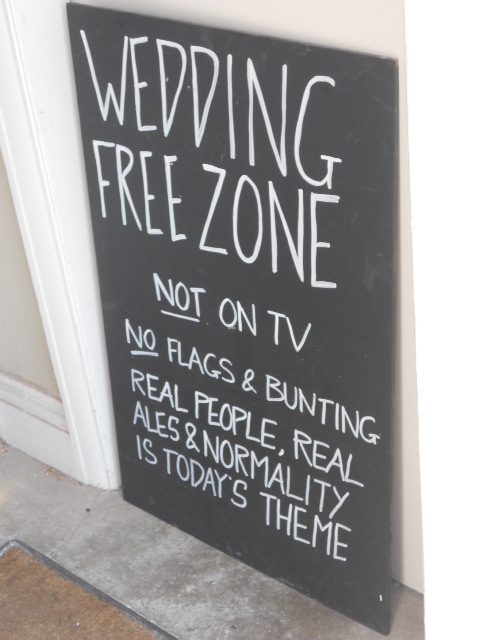

So that's that. John also provided a handout with statistics and so on relevant to the talk, which I'll post in the next week or two. I should probably take this opportunity to plug Solidarity Books itself. Though this was the first of these talks I attended, the consensus is that they have been a resounding success, not least for taking history outside of the Universities and into the public sphere. Incidentally, every speaker has spoken free of charge, many of them travelling down just for the talk. In addition to providing a venue for talks and film showings, the book selection is excellent. There is a wide selection of radical, socialist, anarchist, feminist and republican material Although, unlike its predecessor on Barrack St., there is little in the way of Marxist classics and so on. However, it's the WSM who put the hours in running the place so I can't really complain. In particular, it's worth noting that the selection of Irish history books is, by far and away, the best in the city, eclipsing even Vibes and Scribes on Bridge Street. If you live in Cork be sure to support it. If you're coming from up the country just for a day or a weekend, it's definetely worth making the effort to pay a visit.